Abandoned Communities ..... Dunwich

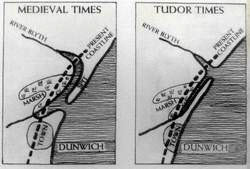

The third way in which the sea would harm Dunwich was by moving Kings Holme, a spit of sand and shingle north east of the town. Kings Holme no longer exists. The shingle that formed it has been pushed into the shore or moved further south along the Suffolk coast, but in the early medieval period it stretched four or five kilometres in a southerly direction from the village of Southwold. The River Blyth, which today goes straight into the sea between Southwold and Walberswick, was diverted by Kings Holme and ran south before emerging into the sea a short distance north of Dunwich.

A similar shingle spit can today be seen at Orford Ness, south of Aldeburgh. If you look at a map you will see that the River Alde is prevented from entering the sea by Orford Ness, and has to run an additional seventeen kilometres before it can discharge itself.

The significance of Kings Holme was that it helped to create the natural harbour that gave rise to Dunwich's prosperity. In addition, ships leaving the villages of Southwold, Walberswick and Blythburgh could reach the sea only by passing close to Dunwich. The people of Dunwich claimed the right to impose charges on any ships passing to and from the villages to the north. At times they went further, for example demanding that ships from elsewhere entering the harbour with goods to trade should use the port facilities at Dunwich and must sell their goods in the market there.

These circumstances inevitably caused much friction between the people of Dunwich and the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages. I will begin the story of the conflict in 1216, when a group of Dunwich men went to Walberswick, set fire to about twelve houses, burnt a chapel belonging to Lady Margery de Cressy, together with the ornaments in the chapel, and "dragged an image of Saint John by its neck as far as Dunwich". Margery de Cressy, a widow, was the lady of the manor of Blythburgh and Walberswick. She responded by suing the men in an ecclesiastical court, but seven years later the case had still not been concluded and in 1223 the men sued her in the king's court in a counterclaim. Margery de Cressy then raised the stakes by suing the bailiffs of Dunwich in the king's court. In 1228 the Dunwich men appeared to gain a decision largely in their favour, but when Margery de Cressy died in 1230 the legal disputes continued.

Rowland Parker has described how a final judgement was reached at a meeting in 1231, and he has produced a full translation of the decision.

See Rowland Parker, Men of Dunwich: The Story of a Vanished Town, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1978.

In essence it was decided that the harbour should be divided, with Dunwich having the right to charge tolls for ships anchoring in the lower part, but Blythburgh having a similar right in the northern section. Moreover, rights said to have been in existence since before the Norman conquest allowing boats to travel freely to the three neighbouring villages were re-affirmed. The decision stated that the people of Dunwich had "maliciously hindered" such free passage.

Copies of this decision would have been given to the people of both Dunwich and Blythburgh. However, the copy given to Blythburgh seems to have been mislaid. Rowland Parker has taken the view that the residents of Blythburgh, Walberswick and Southwold would have known about the document and no doubt remembered its contents, but as they failed to produce their copy when it mattered they were unable to take advantage of it.

One detail of the legal proceedings that should be noted is that Margery de Cressy was instructed not to entice people from Dunwich to go and live in Blythburgh or Walberswick. This ruling strongly suggests that a significant number of people were already thinking about moving out of Dunwich. Any attempts to provide inducements to do so appear to have been resisted by Dunwich as such migration would have been seen as enhancing the power of Blythburgh at the expense of Dunwich.

However, it was inevitable that such a shift of power would be brought about before long by natural forces. Between 1250 and 1328 three major incidents occurred which massively diminished the strength and influence of the town of Dunwich. Early in 1250 the combination of strong north-easterly winds and an unusually high tide accelerated the movement of Kings Holme, and at its southern end it completely blocked the harbour mouth. The River Blyth had to find an alternative exit to the sea. It did so at a point on the coast close to Walberswick. The smaller River Dunwich was diverted northwards and would have joined the Blyth just before it entered the sea.

A similar shingle spit can today be seen at Orford Ness, south of Aldeburgh. If you look at a map you will see that the River Alde is prevented from entering the sea by Orford Ness, and has to run an additional seventeen kilometres before it can discharge itself.

The significance of Kings Holme was that it helped to create the natural harbour that gave rise to Dunwich's prosperity. In addition, ships leaving the villages of Southwold, Walberswick and Blythburgh could reach the sea only by passing close to Dunwich. The people of Dunwich claimed the right to impose charges on any ships passing to and from the villages to the north. At times they went further, for example demanding that ships from elsewhere entering the harbour with goods to trade should use the port facilities at Dunwich and must sell their goods in the market there.

These circumstances inevitably caused much friction between the people of Dunwich and the inhabitants of the neighbouring villages. I will begin the story of the conflict in 1216, when a group of Dunwich men went to Walberswick, set fire to about twelve houses, burnt a chapel belonging to Lady Margery de Cressy, together with the ornaments in the chapel, and "dragged an image of Saint John by its neck as far as Dunwich". Margery de Cressy, a widow, was the lady of the manor of Blythburgh and Walberswick. She responded by suing the men in an ecclesiastical court, but seven years later the case had still not been concluded and in 1223 the men sued her in the king's court in a counterclaim. Margery de Cressy then raised the stakes by suing the bailiffs of Dunwich in the king's court. In 1228 the Dunwich men appeared to gain a decision largely in their favour, but when Margery de Cressy died in 1230 the legal disputes continued.

Rowland Parker has described how a final judgement was reached at a meeting in 1231, and he has produced a full translation of the decision.

See Rowland Parker, Men of Dunwich: The Story of a Vanished Town, Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1978.

In essence it was decided that the harbour should be divided, with Dunwich having the right to charge tolls for ships anchoring in the lower part, but Blythburgh having a similar right in the northern section. Moreover, rights said to have been in existence since before the Norman conquest allowing boats to travel freely to the three neighbouring villages were re-

Copies of this decision would have been given to the people of both Dunwich and Blythburgh. However, the copy given to Blythburgh seems to have been mislaid. Rowland Parker has taken the view that the residents of Blythburgh, Walberswick and Southwold would have known about the document and no doubt remembered its contents, but as they failed to produce their copy when it mattered they were unable to take advantage of it.

One detail of the legal proceedings that should be noted is that Margery de Cressy was instructed not to entice people from Dunwich to go and live in Blythburgh or Walberswick. This ruling strongly suggests that a significant number of people were already thinking about moving out of Dunwich. Any attempts to provide inducements to do so appear to have been resisted by Dunwich as such migration would have been seen as enhancing the power of Blythburgh at the expense of Dunwich.

However, it was inevitable that such a shift of power would be brought about before long by natural forces. Between 1250 and 1328 three major incidents occurred which massively diminished the strength and influence of the town of Dunwich. Early in 1250 the combination of strong north-

Two

Maps showing the coastline near Dunwich in the twelfth century and in the sixteenth century