Abandoned Communities ..... Grahamston

Some impressions of the way of life in Grahamston around the start of the nineteenth century appear in a book called Quiet Old Glasgow, With many interesting matters, giving a Pleasing Account of the Village of Grahamston, published in 1893. The author was Robert Lindsay, though at the front of the book he simply stated that it was by a Burgess of Glasgow. Quiet Old Glasgow is vague on dates and it does not give the sources of its information, but I assume it is based on reliable recollections. Here are some of the topics covered in the book:

• The village schoolmaster, Mr Marshall. Mr Marshall lived in a tenement on the north side of Argyle Street. His school was in Dallas Court on the other side of Argyle Street. He would not allow his pupils to move on in a subject until they had a complete grasp of what they had already learnt. He kept a tawse, a type of whip, but his preferred form of punishment was to place an old brown wig on the offender's head and set him marching through the schoolroom with his right forefinger in his ear and his left in his mouth.

• The introduction of gas lighting. When gas lighting was installed in the Trongate, a short distance east of Grahamston, groups of people would gather to see the new light. They did not always understand how it was produced. Queries recorded by Lindsay included “Whaur dis the lowe come frae?” and “I' thae nae wick intilt?”.

• The Unitarian chapel on the east side of Union street. Within the city itself instrumental music was not used in any places of worship, but on winter Sabbath evenings the Unitarian chapel was popular with young lads and their sweethearts, who went to hear the organ played.

• Open ground behind the tenements in Alston Street. This space was used by housewives for bleaching their clothes. As the tenements did not have a back door the women would climb in and out of a window. The space was also used by schoolboys intent on settling a quarrel. Arguments between two boys might arise during a game of muggie, ringie, or pitch and toss. Another boy might urge them to fecht for't. On one occasion the mother of one of the fighting boys noticed what was happening, climbed out of the window, seized her son by the collar and dragged him back through the window, cuffing his chafts as they went.

• Reading newspapers. As most people could not afford to buy newspapers just for their own use various arrangements were made to read papers on a collective basis. A group of neighbours in a tenement might arrange to have their papers in succession, or they might meet, preferably in a house with no small children, and ask a well educated boy to read the paper to them. Papers might then be returned to the newsagent next morning and sold at half price to a tavern or change-house keeper.

• Fire Balloons. The balloons were made of fine silk paper tapering towards the bottom and with a hook that held a sponge dipped in turpentine. The sponge would be set alight, the balloon would inflate and then rise rapidly into the air. Watching youths would run off in all directions hoping to be the first to catch the balloon when it fell to ground. In due course the practice was banned as it was suspected that the balloons had caused several fires of haystacks and thatched roofs.

Grahamston developed rapidly in the first half of the nineteenth century. Its population grew from 896 in 1791 to 1924 in 1841. Many new businesses were created or moved to Grahamston from Glasgow itself.

One of the new businesses was a sugar refinery owned by Wilson and Co. near the northern end of Alston Street. The building, erected around 1808, was six storeys tall, and at its southern end there was an engine house and chimney rising about ten feet above the gable. There was a major incident on 2 November 1848 when the side walls and north gable of the building suddenly collapsed inwards. Twelve of the eighteen men employed at the refinery were killed, but it took four days to dig through the rubble and retrieve their bodies. A collection organised in the neighbourhood raised £400 for the families of those who died.

According to Norrie Gilliland the refinery was not re-

Another business with premises just off Alston Street was the Glasgow Gas Light Company. The importance of the introduction of good street lighting in Glasgow has been fully described in Norrie Gilliland's book. The company was set up in 1818, but in 1832 the company bought half an acre of land in Grahamston from Misses Margaret and Lillias Campbell. The southern part of the property faced on to Argyle Street, but this was sold soon afterwards to Mr Thomas Cuthbertson, an iron merchant, in a deal that allowed Cuthbertson to block a passage seven feet wide through the building. From that date the Company would rely on access via a lane leading west from Alston Street.

About the same time the Glasgow Gas Light Company was accused of financial malpractice that meant that consumers of gas were paying an unduly high price. A Commission established to examine the company's accounts reported to Glasgow Council in July 1835 that the company was indebted to gas consumers in the sum of £53,778:12:8 as they had failed to reduce prices as required. The Commission recommended that a price reduction of 50% should be enforced for five years, when a further investigation should take place with the possibility of raising the price again.

Three

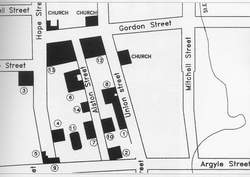

Map of Grahamston, taken from Norrie Gilliland’s book. The sugar refinery is no. 6 and the Glasgow Gas Light Company were at no. 11.